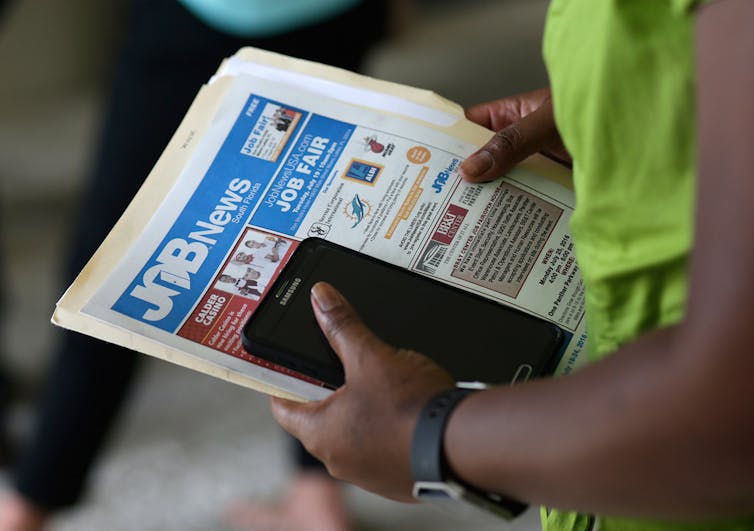

AP Photo/Lynne Sladky

Erin Wolcott, Middlebury College

The unemployment rate has plunged to about the lowest level in half a century. Yet at least one group of Americans is being left behind: men who didn’t go to college.

Just 78 percent of men aged 25-54 who never went to college were employed in 2016, the latest year for which data are available in the American Community Survey. That contrasts with about 90 percent for those who have at least one year of college and is a big change from the 1950s, when employment rates for college and non-college men were the same.

What’s driving the employment gap, which has been with us for decades?

Economists have traditionally pointed the finger at what are known as demand-side factors, such as jobs moving out of the U.S. or robots. More recently, economists have been blaming the supply side, such as growing welfare payments and better video games that glue more men to their couches.

Supply side just means that the explanation has to do with the individual – the supplier of labor — as opposed to something related to a company – the demand.

My research attempts to get to the bottom of why non-college men aren’t working in hopes that it can suggest the right solutions to turn this around.

AP Photo/Kamil Zihnioglu

Employment vs. unemployment

One of the most important measures of an economy is the number of jobs it’s creating, typically measured by the unemployment rate. The latest jobs report, which came out on June 1, showed that the rate dipped to 3.8 percent in May, the lowest since 2000. If it falls any more, it’ll be the lowest since 1969.

But the unemployment rate doesn’t tell the full story because it only includes people actively looking for work. People who report not having looked for work in the previous four weeks are completely left out of this number. The employment rate, which is the share who are actually employed, captures the full picture.

And the numbers are stark. Back in the 1950s, there was no education-based gap in employment. About 90 percent of men aged 25-54 – regardless of whether they went to college – were employed. That began to change in the 70s and 80s as non-college men left the workforce.

The Great Recession was particularly painful for men without any college. By 2010, only 74 percent had a job, compared with 87 percent of those with a year or more of college.

In other words, employment rates diverged over 10 percentage points in just half a century.

The gap extends to the wages of those who actually had jobs as well. As recently as 1980, real hourly wages for the two groups were nearly identical at about US$13. In 2015, men with at least a little college saw their wages soar 65 percent to over $22 an hour. Meanwhile, pay for those who never attended plunged by almost half to less than $8.

Modeling the economy

In fact, wages reveal the answer to this puzzle.

In my analysis, which I’m planning to publish, I wanted to determine whether the widening employment rate gap was caused by factors related to the supply of workers — video games and welfare — or demand — trade and robots.

So I built and calibrated an economic model aimed at finding the answer. Just as an architect builds a model city to test out ideas, economists build model economies out of math. Models allow architects and economists alike to push aside the gory details of reality and cut to the gist of things.

They also allow us to run experiments on what would otherwise be untestable hypotheses. An architect might ask: If I build a balcony, will that compromise the building’s structural integrity? I asked: If the only things that changed since the 1970s were supply-side factors, what would have happened to employment rates?

To answer this question, I plugged employment, wage and other relevant data into my model so that it replicates the real world. I then ran different analyses on the model to try to learn things, such as the underlying causes of the fall in employment for non-college men.

The intuition is like this: If a significant part of the reason non-college men dropped out of the workforce was because of supply-side factors that allowed them to remain home yet still afford their lifestyles, companies would have had to pay them more to entice them to join the labor market. On the other hand, demand-side factors would have put downward pressure on wages.

That’s exactly what my model helped me identify, suggesting that all the blame goes to demand-side factors like trade and automation, not video games.

An important caveat with my analysis — and economic research in general — is that our models are not reality. Economists have to make tough judgment calls in hopes of approximating reality and teasing out underlying truths that are otherwise difficult to ascertain.

Work wanted

All the same, I think my work reveals some important truths.

While it is true that many non-college men are home playing video games, collecting welfare payments and, unfortunately, addicted to opioids, it’s by and large not because they are choosing these over a job. Rather, sadly, it’s because they couldn’t find a job in the first place.

The takeaway is if the government wants to get more of these men back into the workforce, it should focus on stimulating demand or helping people learn new skills.

![]() Even though we know what the problem is, we still have a lot of work ahead to solve it and get these men back into the workforce.

Even though we know what the problem is, we still have a lot of work ahead to solve it and get these men back into the workforce.

Erin Wolcott, Assistant Professor of Economics, Middlebury College

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Recent Comments